Abstracto

Recientemente, se investigaron los orígenes geográficos de los judíos asquenazíes (AJ) y su lengua materna, el yidis, aplicando la Estructura Geográfica de la Población (GPS) a una cohorte de AJ exclusivamente hablantes de yidis y multilingües. El GPS localizó a la mayoría de los AJ a lo largo de las principales rutas comerciales antiguas del noreste de Turquía, junto a aldeas primigenias con nombres que se asemejan a la palabra "Ashkenaz". Estos hallazgos fueron compatibles con la hipótesis de un origen irano-turco-eslavo para los AJ y un origen eslavo para el yidis, y contradecían la hipótesis de Renania, que abogaba por un origen levantino para los AJ y un origen alemán para el yidis. Analizamos cómo estos hallazgos impulsan tres debates en curso sobre (1) el significado histórico del término "Ashkenaz"; (2) la estructura genética de los AJ y sus orígenes geográficos, tal como se infiere de múltiples estudios que emplean análisis de ADN moderno y antiguo, y de ADN antiguo original; y (3) el desarrollo del yidis. Proporcionamos validación adicional al origen no levantino de los AJ utilizando ADN antiguo de Oriente Próximo y el Levante. Debido a la creciente popularidad de las herramientas de geolocalización para abordar cuestiones de origen, analizamos brevemente las ventajas y limitaciones de las herramientas más populares, centrándonos en el enfoque GPS. Nuestros resultados refuerzan el origen no levantino de los AJ.

Palabras clave: yidis, judíos asquenazíes, asquenazí, estructura geográfica de la población (GPS), arqueogenética, hipótesis de Renania, ADN antiguo

Fondo

El origen geográfico de los “Ashkenaz” bíblicos, los judíos asquenazíes (AJ) y el yiddish son unas de las preguntas más antiguas de la historia, la genética y la lingüística.

Las incertidumbres sobre el significado de «Asquenazí» surgieron en el siglo XI, cuando el término pasó de ser una designación de los escitas iraníes a la de los eslavos y germanos, y finalmente de los judíos «alemanes» (asquenazíes) entre los siglos XI y XIII (Wexler, 1993 ). La primera discusión conocida sobre el origen de los judíos alemanes y el yidis surgió en los escritos del gramático hebreo Elia Baxur en la primera mitad del siglo XVI (Wexler, 1993 ).

Está bien establecido que la historia también se refleja en el ADN a través de las relaciones entre la genética, la geografía y el lenguaje (p. ej., Cavalli-Sforza, 1997 ; Weinreich, 2008 ). Max Weinreich, el decano del campo de la lingüística yidis moderna, ya ha enfatizado la verdad de que la historia del yidis refleja la historia de sus hablantes. Estas relaciones impulsaron a Das et al. ( 2016 ) a abordar la cuestión del origen yidis mediante el análisis de los genomas de los AJ de habla yidis, los AJ multilingües y los judíos sefardíes utilizando la Estructura Geográfica de la Población (GPS), que localiza los genomas en el lugar donde experimentaron el último evento importante de mezcla. El GPS rastreó casi todos los AJ hasta las principales rutas comerciales antiguas en el noreste de Turquía adyacentes a cuatro aldeas primigenias cuyos nombres se parecen a "Ashkenaz": İşkenaz (o Eşkenaz), Eşkenez (o Eşkens), Aşhanas y Aschuz. Evaluados a la luz de las hipótesis de Renania e Irano-Turco-Eslava (Das et al., 2016 , Tabla 1 ), los hallazgos respaldaron esta última, lo que implica que el yidis fue creado por comerciantes judíos eslavo-iraníes que navegaban por las Rutas de la Seda. Analizamos estos hallazgos desde perspectivas históricas, genéticas y lingüísticas y calculamos la similitud genética de los AJ y las poblaciones de Oriente Medio con los genomas antiguos de Anatolia, Irán y el Levante. Por último, revisamos brevemente las ventajas y limitaciones de las herramientas de biolocalización y su aplicación en la investigación genética.

Tabla 1.

Grandes preguntas abiertas sobre el origen del término “Ashkenaz”, los AJ y el yiddish, explicadas desde dos hipótesis en pugna.

La evidencia genética producida por Das et al. ( 2016 ) se muestra en la última columna .

El significado histórico de Ashkenaz

“Asquenaz” es uno de los topónimos bíblicos más controvertidos. Aparece en la Biblia hebrea como el nombre de uno de los descendientes de Noé (Génesis 10:3) y como referencia al reino de Asquenaz, profetizado para ser convocado junto con Ararat y Minnai para librar una guerra contra Babilonia (Jeremías 51:27). Además de rastrear a los AJ hasta las antiguas tierras iraníes de Asquenaz y descubrir las aldeas cuyos nombres pueden derivar de “Asquenaz”, el origen iraní parcial de los AJ, inferido por Das et al. ( 2016 ), fue respaldado además por la similitud genética de los AJ con los judíos sefardíes de las montañas y los judíos iraníes, así como su similitud con las poblaciones del Cercano Oriente y las poblaciones turcas y caucásicas “nativas” simuladas.

Existen buenas razones, por lo tanto, para inferir que los judíos que se consideraban asquenazíes adoptaron este nombre y hablaban de sus tierras como asquenazíes, ya que se percibían a sí mismos como de origen iraní. El hecho de que encontremos evidencia variada del conocimiento de la lengua iraní entre los judíos marroquíes y andaluces y los caraítas antes del siglo XI es un punto de referencia convincente para evaluar los orígenes iraníes compartidos de los judíos sefardíes y asquenazíes (Wexler, 1996 ). Además, los judíos de habla iraní en el Cáucaso (los llamados juhuris) y los judíos de habla turca en Crimea antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial se llamaban a sí mismos "asquenazíes" (Weinreich, 2008 ).

La hipótesis de Renania no puede explicar por qué un nombre que denota "escitas" y estaba asociado con el Cercano Oriente se asoció con tierras alemanas entre los siglos XI y XIII (Wexler, 1993 ). Aptroot ( 2016 ) sugirió que los inmigrantes judíos en Europa transfirieron nombres bíblicos a las regiones en las que se asentaron. Esto no es convincente. Los nombres bíblicos se usaban como topónimos solo cuando tenían sonidos similares. No solo Alemania y Ashkenaz no comparten sonidos similares, sino que Alemania ya se llamaba "Germana" o "Germamja" en el Talmud iraní ("babilónico") (completado en el siglo V d. C.) y, como era de esperar, se asoció con el nieto de Noé, Gomer (Talmud, Yoma 10a). La adopción de nombres también se produjo cuando los topónimos exactos estaban en duda, como en el caso de Sefarad (España). Este no es el caso aquí, como también señala Aptroot, ya que “Ashkenaz” tenía una afiliación geográfica conocida y clara (Tabla 1 ). Finalmente, Alemania era conocida por los eruditos franceses como el RaDaK (1160-1235) como “Almania” (Sp. Alemania, Fr. Allemagne), en honor a las tribus almani, un término que también fue adoptado por los eruditos árabes. Si el erudito francés Rashi (1040?-1105), hubiera interpretado aškenaz como “Alemania”, habría sido conocido por el RaDaK que usó los símbolos de Rashi. Por lo tanto, la propuesta de Wexler de que Rashi usó aškenaz en el significado de “eslavo” y que el término aškenaz asumió el significado solitario de “tierras alemanas” solo después del siglo XI en Europa Occidental como resultado del auge del yidis, es más razonable (Wexler, 2011 ). Esto también se ve respaldado por los importantes hallazgos de Das et al. sobre las únicas aldeas primigenias conocidas cuyos nombres derivan de la palabra «Asquenaz», ubicadas en las antiguas tierras de Asquenaz. Por lo tanto, nuestra inferencia se sustenta en evidencia histórica, lingüística y genética, que tiene mayor peso como un origen simple y fácilmente explicable que como un escenario más complejo que implica múltiples translocaciones.

La estructura genética de los judíos asquenazíes

Los AJ se localizaron en la actual Turquía y se descubrió que eran genéticamente más cercanos a las poblaciones turcas, del sur del Cáucaso e iraníes, lo que sugiere un origen común en las tierras iraníes "ashkenazíes" (Das et al., 2016 ). Estos hallazgos fueron más compatibles con un origen irano-turco-eslavo para los AJ y un origen eslavo para el yidis que con la hipótesis de Renania, que carece de respaldo histórico, genético y lingüístico (Tabla 1 ) (van Straten, 2004 ; Elhaik, 2013 ). Los hallazgos también han resaltado los fuertes vínculos socioculturales y genéticos del judaísmo asquenazí e iraní y sus orígenes iraníes compartidos (Das et al., 2016 ).

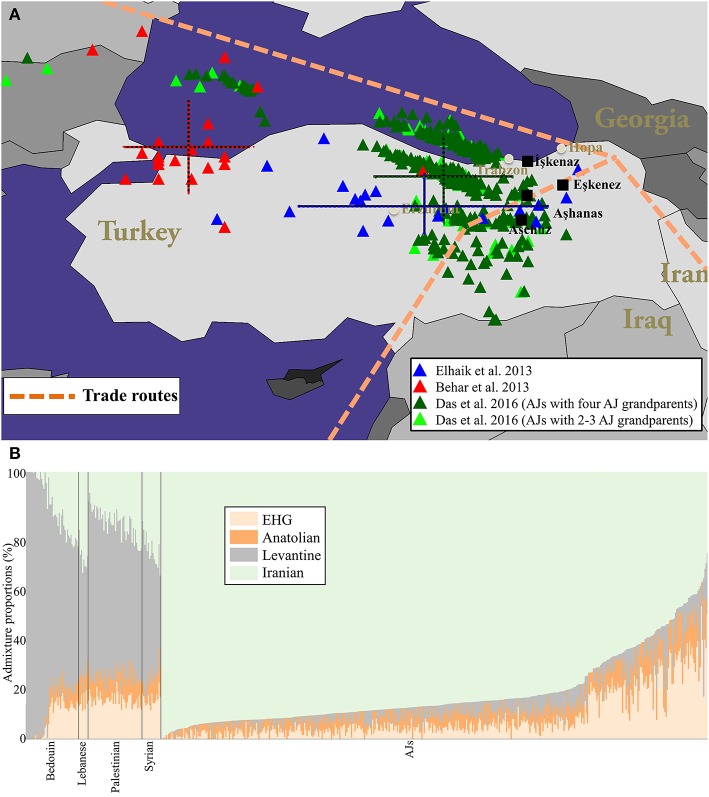

Hasta ahora, todos los análisis destinados a geolocalizar los AJ (Behar et al., 2013 , Figura 2B; Elhaik, 2013 , Figura 4; Das et al., 2016 , Figura 4) identificaron a Turquía como el origen predominante de los AJ, aunque utilizaron diferentes enfoques y conjuntos de datos, en apoyo de la hipótesis irano-turco-eslava (Figura 1A , Tabla 1 ). La existencia de ancestros importantes del sur de Europa y del Cercano Oriente en los genomas de los AJ también son fuertes indicadores de la hipótesis irano-turco-eslava, siempre que se tenga en cuenta la historia grecorromana de la región al sur del Mar Negro (Baron, 1937 ; Kraemer, 2010 ). Recientemente, Xue et al. ( 2017 ) aplicaron GLOBETROTTER a un conjunto de datos de 2540 AJ genotipados en 252 358 SNP. El perfil de ascendencia inferido para los AJ fue 5% Europa Occidental, 10% Europa Oriental, 30% Levante y 55% Europa Meridional (los autores no consideraron una ascendencia de Oriente Próximo). Elhaik ( 2013 ) retrató un perfil similar para los judíos europeos, que consiste en un 25-30% de Oriente Medio y grandes ascendencias de Oriente Próximo-Cáucaso (32-38%) y Europa Occidental (30%). Notablemente, Xue et al. ( 2017 ) también infirieron un "tiempo de mezcla" de 960-1.416 d. C. (hace ≈24-40 generaciones), que corresponde al momento en que los AJ experimentaron grandes cambios geográficos a medida que el reino jázaro judaizado disminuía y sus redes comerciales colapsaban, obligándolos a reubicarse en Europa (Das et al., 2016 ). El límite inferior de esa fecha corresponde al momento en que se originó el yidis eslavo, hasta donde sabemos.

Figura 1.

La localización de los AJ y sus proporciones de mezcla antigua en comparación con las poblaciones vecinas. (A) Predicciones geográficas de individuos analizados en tres estudios separados que emplean diferentes herramientas: Elhaik ( 2013 , Figura 4) (azul), Behar et al. ( 2013 , Figura 2B) (rojo) y Das et al. ( 2016 , Figura 4) (verde oscuro para los AJ que tienen cuatro abuelos AJ y verde claro para el resto) se muestran. Se muestran la media y la desviación estándar (barras) de coincidencia de color de la longitud y la latitud para cada cohorte. Dado que no tuvimos éxito en obtener los puntos de datos de Behar et al. ( 2013 , Figura 2B) del autor correspondiente, obtuvimos el 78% de los puntos de datos de su figura. Debido a la baja calidad de su figura, no pudimos extraer de manera confiable los puntos de datos restantes. (B) Resultados de ADMIXTURE supervisados. Para abreviar, se agruparon las subpoblaciones. El eje x representa los individuos. Cada individuo está representado por una columna vertical apilada con proporciones de mezcla codificadas por colores que reflejan las contribuciones genéticas de los antiguos cazadores-recolectores, anatolios, levantinos e iraníes.

El origen no levantino de los AJ se ve respaldado además por un antiguo análisis de ADN de seis natufianos y un neolítico levantino (Lazaridis et al., 2016 ), algunos de los progenitores judíos más probables (Finkelstein y Silberman, 2002 ; Frendo, 2004 ). En un análisis de componentes principales (PCA), los antiguos levantinos se agruparon predominantemente con los palestinos y beduinos modernos y se superpusieron marginalmente con los judíos árabes, mientras que los AJ se agruparon lejos de los individuos levantinos y adyacentes a los anatolios neolíticos y los europeos del Neolítico tardío y de la Edad del Bronce. Para evaluar estos hallazgos, inferimos las antiguas ascendencias de los AJ utilizando el análisis de mezcla descrito en Marshall et al. ( 2016 ). Brevemente, analizamos 18.757 SNP autosómicos genotipados en 46 palestinos, 45 beduinos, 16 sirios y ocho libaneses (Li et al., 2008 ) junto con 467 AJ [367 AJ analizados previamente y 100 individuos con madre AJ] (Das et al., 2016 ) que se superponían tanto con el GenoChip (Elhaik et al., 2013 ) como con los datos de ADN antiguo (Lazaridis et al., 2016 ). Luego, realizamos un análisis ADMIXTURE supervisado (Alexander y Lange, 2011 ) utilizando tres cazadores-recolectores de Europa del Este de Rusia (EHG) junto con seis levantinos epipaleolíticos, 24 anatolios neolíticos y seis iraníes neolíticos como poblaciones de referencia (Tabla S0 ). Sorprendentemente, los AJ exhiben un iraní dominante (

El debate lingüístico sobre la formación del yiddish

La hipótesis de que el yidis tiene un origen alemán ignora la mecánica de la relexificación, el proceso lingüístico que produjo el yidis y otras lenguas "judías antiguas" (es decir, las creadas entre los siglos IX y X). Comprender cómo funciona la relexificación es esencial para comprender la evolución de las lenguas. Este argumento tiene un contexto similar al de la evolución del vuelo propulsado. Rechazar la teoría de la evolución puede llevar a concluir que las aves y los murciélagos son parientes cercanos. Al ignorar la literatura sobre la relexificación y la historia judía en la Alta Edad Media, los autores (p. ej., Aptroot, 2016 ; Flegontov et al., 2016 ) llegan a conclusiones que tienen un respaldo histórico débil. La ventaja de un análisis de geolocalización es que nos permite inferir el origen geográfico de los hablantes de yidis, dónde residieron y con quién se mezclaron, independientemente de las controversias históricas, lo que proporciona una visión basada en datos sobre la cuestión de los orígenes geográficos. Esto permite una revisión objetiva de las posibles influencias lingüísticas en el yiddish (Tabla 1 ), lo que expone los peligros de adoptar una visión de “creacionismo lingüístico” en lingüística.

La evidencia histórica a favor de un origen irano-turco-eslavo para el yidis es primordial (p. ej., Wexler, 1993 , 2010 ). Los judíos desempeñaron un papel importante en las Rutas de la Seda en los siglos IX al XI. A mediados del siglo IX, aproximadamente en los mismos años, los comerciantes judíos tanto en Maguncia como en Xi'an recibieron privilegios comerciales especiales del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico y la corte de la dinastía Tang (Robert, 2014 ). Estas rutas unían Xi'an con Maguncia y Andalucía, y más allá con el África subsahariana y a través de la Península Arábiga e India-Pakistán. Las Rutas de la Seda proporcionaron la motivación para el asentamiento judío en Afro-Eurasia en los siglos IX al XI, ya que los judíos desempeñaron un papel dominante en estas rutas como un gremio comercial neutral sin agendas políticas (Gil, 1974 ; Cansdale, 1996 , 1998 ). Por lo tanto, los comerciantes judíos tuvieron contacto con una riqueza de idiomas en las áreas que atravesaron (Hadj-Sadok, 1949 ; Khordadhbeh, 1889 ; Hansen, 2012 ; Wexler TBD), que trajeron de regreso a sus comunidades anidadas en los principales centros comerciales (Rabinowitz, 1945 , 1948 ; Das et al., 2016 ). Las Rutas de la Seda de Eurasia central estaban controladas por las políticas iraníes, que brindaron oportunidades para los judíos de habla iraní, que constituyeron la abrumadora mayoría de los judíos del mundo desde la época de Cristo hasta el siglo XI (Baron, 1952 ). No debería sorprendernos descubrir que el yidis (y otras lenguas judías antiguas) contiene componentes y reglas de una gran variedad de idiomas, todos ellos hablados en las Rutas de la Seda (Khordadhbeh, 1889 ; Wexler, 2011 , 2012 , 2017 ).

Además de los contactos lingüísticos, las Rutas de la Seda también motivaron la conversión generalizada al judaísmo por parte de poblaciones deseosas de participar en el comercio extremadamente lucrativo, que se había convertido en un cuasi monopolio judío a lo largo de las rutas comerciales (Rabinowitz, 1945 , 1948 ; Baron, 1957 ). Estas conversiones se analizan en la literatura judía entre los siglos VI y XI, tanto en Europa como en Irak (Sand, 2009 ; Kraemer, 2010 ). El yidis y otras lenguas judías antiguas fueron creadas por los comerciantes peripatéticos como lenguas secretas que los aislarían de sus clientes y socios comerciales no judíos (Hadj-Sadok, 1949 ; Gil, 1974 ; Khordadhbeh, 1889 ; Cansdale, 1998 ; Robert, 2014 ). El estudio del génesis del yiddish, por tanto, requiere el estudio de todas las antiguas lenguas judías de este período de tiempo.

También hay una cantidad cuantificable de elementos iraníes y turcos en el yidis. El Talmud de Babilonia, completado en el siglo VI d. C., es rico en influencias lingüísticas, legalistas y religiosas iraníes. Desde el Talmud, un amplio vocabulario iraní ha ingresado al hebreo y al judeoarameo, y de allí se extendió al yidis. Este corpus se conoce desde la década de 1930 y es de conocimiento común para los estudiosos del Talmud (Telegdi, 1933 ). En el Imperio Jázaro, los judíos euroasiáticos, que recorrían las Rutas de la Seda, se convirtieron en hablantes de eslavo, un idioma importante debido a las actividades comerciales de los rus (preucranianos) con quienes los judíos estaban indudablemente aliados en las rutas que unían Bagdad y Baviera. Esto es evidente por la existencia del hebroidismo de reciente invención, inspirado en los patrones eslavos del discurso en yidis (Wexler, 2010 ).

Abogamos por una comprensión más evolutiva de la lingüística. Esto incluye prestar mayor atención a los procesos lingüísticos que alteran las lenguas (por ejemplo, la relexificación) y adquirir mayor competencia en otras lenguas e historias. Al estudiar el origen de los judíos asquenazíes y el yidis, dicho conocimiento debe incluir la historia de las Rutas de la Seda y las lenguas irano-turcas.

Inferencia de orígenes geográficos

Descifrar el origen de las poblaciones humanas no es un desafío nuevo para los genetistas, pero solo en la última década se aprovecharon los datos genéticos de alto rendimiento para responder a estas preguntas. Aquí, discutimos brevemente las diferencias entre las herramientas disponibles basadas en la identidad por distancia. Los enfoques PCA o similares a PCA existentes (p. ej., Novembre et al., 2008 ; Yang et al., 2012 ) pueden localizar a los europeos en países (entendidos como el último lugar donde tuvo lugar un evento de mezcla importante o el lugar de donde vinieron los cuatro ancestros de los individuos "no mezclados") con menos del 50% de precisión (Yang et al., 2012 ). Las limitaciones del PCA (discutidas en Novembre y Stephens, 2008 ) parecen ser inherentes al marco donde las poblaciones continentales trazadas a lo largo de los dos PC primarios se agrupan en los vértices de una forma similar a un triángulo y las poblaciones restantes se agrupan a lo largo o dentro de los bordes (p. ej., Elhaik et al., 2013 ). Por lo tanto, existen motivos para cuestionar la aplicabilidad de métodos ambiciosos basados en PCA (Yang et al., 2012 , 2014 ) que buscan inferir múltiples ubicaciones ancestrales fuera de Europa. En general, la localización precisa de individuos en todo el mundo sigue siendo un desafío significativo (Elhaik et al., 2014 ).

El marco GPS asume que los humanos son mixtos y que su variación genética (mezcla) puede modelarse por la proporción de genotipos asignados a cualquier número de poblaciones ancestrales putativas regionales fijas (Elhaik et al., 2014 ). GPS emplea un análisis ADMIXTURE supervisado donde los componentes de mezcla son fijos, lo que permite evaluar tanto a los individuos de prueba como a las poblaciones de referencia contra las mismas poblaciones ancestrales putativas . GPS infiere las coordenadas geográficas de un individuo al hacer coincidir sus proporciones de mezcla con las de las poblaciones de referencia . Las poblaciones de referencia son poblaciones que se sabe que residen en una cierta región geográfica durante un período de tiempo sustancial en un marco de tiempo de cientos a mil años y se pueden predecir sus ubicaciones geográficas mientras están ausentes del panel de población de referencia (Das et al., 2016 ). La ubicación geográfica final de un individuo de prueba se determina convirtiendo la distancia genética del individuo a m poblaciones de referencia en distancias geográficas (Elhaik et al., 2014 ). Intuitivamente, se puede pensar que las poblaciones de referencia "atraen" al individuo hacia sí con una fuerza proporcional a su similitud genética hasta que se alcanza un consenso (Figura S1 ). La interpretación de los resultados, en particular cuando la ubicación predicha difiere de la ubicación actual de la población estudiada, requiere cautela.

La estructura poblacional se ve afectada por procesos biológicos y demográficos como la deriva genética, que puede actuar rápidamente en poblaciones pequeñas y relativamente aisladas, a diferencia de las grandes poblaciones no aisladas, y la migración, que ocurre con mayor frecuencia (Jobling et al., 2013 ). Comprender las relaciones entre geografía y mezcla requiere saber cómo el aislamiento relativo y la historia de la migración afectaron las frecuencias alélicas de las poblaciones. Desafortunadamente, a menudo carecemos de información sobre ambos procesos. GPS aborda este problema analizando las proporciones relativas de mezcla en una red global de poblaciones de referencia que nos brindan diferentes "instantáneas" de eventos históricos de mezcla. Estos eventos globales de mezcla ocurrieron en diferentes momentos a través de diferentes procesos biológicos y demográficos, y su efecto duradero está relacionado con nuestra capacidad para asociar a un individuo con su evento de mezcla coincidente.

En poblaciones relativamente aisladas, el evento de mezcla probablemente sea antiguo, y el GPS localizaría a un individuo de prueba con su población parental con mayor precisión. Por el contrario, si el evento de mezcla fue reciente y la población no mantuvo un aislamiento relativo, la predicción del GPS sería errónea (Figura S2 ). Este es el caso de las poblaciones caribeñas, cuyas proporciones de mezcla aún reflejan los eventos de mezcla masivos de los siglos XIX y XX que involucraron a nativos americanos, europeos occidentales y africanos (Elhaik et al., 2014 ). Si bien el nivel original de aislamiento sigue siendo desconocido, estos dos escenarios pueden distinguirse comparando las proporciones de mezcla del individuo de prueba y las poblaciones adyacentes. Si esta similitud es alta, podemos concluir que hemos inferido la ubicación probable del evento de mezcla que dio forma a la proporción de mezcla del individuo de prueba. Si lo contrario es cierto, el individuo está mezclado y, por lo tanto, viola los supuestos del modelo GPS o las poblaciones parentales no existen ni en el panel de referencia del GPS ni en la realidad. La mayoría de las veces (83%) el GPS predijo que los individuos no mezclados estaban en sus ubicaciones reales, y que la mayoría de los individuos restantes estaban en países vecinos (Elhaik et al., 2014 ).

Para entender cómo la migración modifica las proporciones de mezcla de las poblaciones migratorias y anfitrionas, podemos considerar dos casos simples de migración puntual o masiva seguida de asimilación y un tercer caso de migración seguida de aislamiento. Los eventos de migración puntual tienen poco efecto en las proporciones de mezcla de la población anfitriona, particularmente cuando absorbe una escasez de migrantes, en cuyo caso las proporciones de mezcla de los migrantes se asemejarían a las de la población anfitriona dentro de unas pocas generaciones y su lugar de descanso representaría el de la población anfitriona. Los movimientos demográficos masivos, como la invasión o migración a gran escala que afectan a una gran parte de la población son raros y crean cambios temporales en las proporciones de mezcla de la población anfitriona. La población anfitriona aparecería temporalmente como una población mixta bidireccional, reflejando los componentes de las poblaciones anfitriona e invasora (por ejemplo, europeos y nativos americanos, en el caso de los puertorriqueños) hasta que las proporciones de mezcla se homogeneizaran a nivel poblacional. Si se completa este proceso, la firma de mezcla de esta región puede alterarse y la ubicación geográfica de la población anfitriona representaría nuevamente el último lugar donde tuvo lugar el evento de mezcla tanto para la población anfitriona como para la invasora. El GPS, por lo tanto, predeciría la ubicación de la población anfitriona para ambas poblaciones. Se predeciría que las poblaciones que migran de A a B y mantienen el aislamiento genético apuntarían a A en el análisis de población de exclusión. Si bien las migraciones humanas no son poco comunes, mantener un aislamiento genético perfecto durante un largo período de tiempo es muy difícil (p. ej., Veeramah et al., 2011 ; Behar et al., 2012 ; Elhaik, 2016 ; Hellenthal et al., 2016 ), y las predicciones del GPS para la gran mayoría de las poblaciones mundiales indican que estos casos son de hecho excepcionales (Elhaik et al., 2014 ). A pesar de sus ventajas, el GPS tiene varias limitaciones. Primero, produce las predicciones más precisas para individuos no mezclados. En segundo lugar, el uso de poblaciones migratorias o muy mixtas (ambas detectables mediante el análisis poblacional de exclusión de uno) como poblaciones de referencia puede sesgar las predicciones. Se requieren más avances para superar estas limitaciones y que el GPS sea aplicable a grupos de población mixtos (p. ej., afroamericanos).

Conclusión

El significado del término “Ashkenaz” y los orígenes geográficos de los AJ y el yidis son algunas de las preguntas más antiguas en la historia, la genética y la lingüística. En nuestro trabajo anterior hemos identificado el “antiguo Ashkenaz”, una región en el noreste de Turquía que alberga cuatro aldeas primigenias cuyos nombres se parecen a Ashkenaz. Aquí, profundizamos en el significado de este término y argumentamos que adquirió su significado moderno solo después de que una masa crítica de judíos asquenazíes llegó a Alemania. Mostramos que todos los análisis de biolocalización han localizado a los AJ en Turquía y que los orígenes no levantinos de los AJ están respaldados por análisis de genomas antiguos. En general, estos hallazgos son compatibles con la hipótesis de un origen irano-turco-eslavo para los AJ y un origen eslavo para el yidis y contradicen las predicciones de la hipótesis de Renania que carece de respaldo histórico, genético y lingüístico (Tabla 1 ).

Contribuciones del autor

EE concibió el artículo. MP procesó los datos de ADN antiguo. RD y EE realizaron los análisis. EE lo coescribió con PW y RD. Todos los autores aprobaron el artículo.

Declaración de conflicto de intereses

EE es consultor del Centro de Diagnóstico de ADN. Los demás autores declaran que la investigación se realizó sin ninguna relación comercial o financiera que pudiera interpretarse como un posible conflicto de intereses. El revisor PF declaró al editor responsable una coautoría previa con uno de los autores, quien garantizó que el proceso cumpliera con los estándares de una revisión justa y objetiva.

Expresiones de gratitud

EE recibió apoyo parcial del Premio de Intercambio Internacional de la Royal Society a EE y Michael Neely (IE140020), del Premio del Programa de Confianza en el Concepto MRC 2014 de la Universidad de Sheffield a EE (Ref.: MC_PC_14115) y de una subvención DEB-1456634 de la National Science Foundation a Tatiana Tatarinova y EE. Agradecemos a los numerosos participantes públicos por donar sus secuencias de ADN para estudios científicos y a la base de datos pública del Proyecto Genográfico por proporcionarnos sus datos.

Material complementario

El material complementario de este artículo se puede encontrar en línea en: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fgene.2017.00087/full#supplementary-material

Referencias

- Alexander DH, Lange K. (2011). Mejoras del algoritmo ADMIXTURE para la estimación de la ascendencia individual. BMC Bioinformatics 12:246. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-246 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Aptroot M. (2016). Lengua yidis y judíos asquenazíes: una perspectiva desde la cultura, la lengua y la literatura. Genome Biol. Evol. 8, 1948-1949. 10.1093/gbe/evw131 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Atzmon G., Hao L., Pe'er I., Velez C., Pearlman A., Palamara PF, et al. (2010). Los hijos de Abraham en la era del genoma: las principales poblaciones de la diáspora judía comprenden grupos genéticos distintos con ascendencia compartida de Oriente Medio. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 86, 850–859. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.015 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Barón SW (1937). Historia social y religiosa de los judíos, vol. 1, Nueva York, NY: Columbia University Press. [ Google Académico ]

- Baron SW (1952). Historia social y religiosa de los judíos, vol. 2, Nueva York, NY: Columbia University Press. [ Google Académico ]

- Barón SW (1957). Historia social y religiosa de los judíos, vol. 3. Alta Edad Media: Herederos de Roma y Persia. Nueva York, NY: Columbia University Press. [ Google Académico ]

- Behar DM, Harmant C., Manry J., van Oven M., Haak W., Martinez-Cruz B., et al. (2012). El paradigma vasco: evidencia genética de una continuidad materna en la región franco-cantábrica desde el preneolítico. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 486–493. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.002 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Behar DM, Metspalu M., Baran Y., Kopelman NM, Yunusbayev B., Gladstein A., et al. (2013). No hay evidencia, a partir de datos genómicos completos, de un origen jázaro para los judíos asquenazíes. Hum . Biol. 85, 859–900. 10.3378/027.085.0604 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Ben-Sasson HH (1976). Una historia del pueblo judío. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Google Académico ]

- Cansdale L. (1996). Los radhanitas: comerciantes judíos internacionales del siglo IX. Aust. J. Jewish Stud. 10, 65–77. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cansdale L. (1998). Judíos en la Ruta de la Seda, en Mundos de las Rutas de la Seda: Antiguos y Modernos, eds. Christian D., Benjamin C. (Turnhout: Brepols; ), 23–30. 10.1484/M.SRS-EB.4.00037 [ DOI ] [ Google Académico ]

- Cavalli-Sforza LL (1997). Genes, pueblos y lenguas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 7719–7724. 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7719 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Das R., Wexler P., Pirooznia M., Elhaik E. (2016). Localización de judíos asquenazíes en aldeas primigenias en las antiguas tierras iraníes de Asquenazí. Genome Biol. Evol. 8, 1132–1149. 10.1093/gbe/evw046 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Elhaik E. (2013). El eslabón perdido de la ascendencia judía europea: Contrastando las hipótesis de Renania y Jázara. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 61–74. 10.1093/gbe/evs119 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Elhaik E. (2016). En busca del tipo judío : un punto de referencia propuesto para evaluar la base genética del judaísmo desafía las nociones de «biomarcadores judíos». Front. Genet. 7:141. 10.3389/fgene.2016.00141 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Elhaik E., Greenspan E., Staats S., Krahn T., Tyler-Smith C., Xue Y., et al. (2013). El GenoChip: una nueva herramienta para la antropología genética. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 1021–1031. 10.1093/gbe/evt066 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Elhaik E., Tatarinova T., Chebotarev D., Piras IS, Maria Calò C., De Montis A., et al. (2014). El análisis de la estructura geográfica de la población de las poblaciones humanas en todo el mundo infiere sus orígenes biogeográficos. Nat . Comunitario. 5:3513 10.1038/ncomms4513 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Falk R. (2006). Sionismo y la biología de los judíos (hebreo). Tel Aviv: Resling. [ Google Scholar ]

- Finkelstein I., Silberman NA (2002). La Biblia Desenterrada: La Nueva Visión Arqueológica del Antiguo Israel y el Origen de sus Textos Sagrados. Nueva York, NY: Simon and Schuster. [ Google Académico ]

- Flegontov P., Kassian A., Thomas MG, Fedchenko V., Changmai P., Starostin G., et al. (2016). Dificultades del enfoque de la estructura geográfica de la población (GPS) aplicado a la historia genética humana: un estudio de caso de judíos asquenazíes. Genome Biol. Evol. 8, 2259–2265. 10.1093/gbe/evw162 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Frendo AJ (2004). De vuelta a lo básico: un enfoque holístico del problema del surgimiento del antiguo Israel, en busca del Israel preexílico, ed. Day J. (Nueva York, NY: T&T Clark International), 41–64. 10.1097/00152193-200410000-00004 [ DOI ] [ Google Académico ]

- Gil M. (1974). Los comerciantes radhánitas y la tierra de Radhán. J. Econ. Soc. Hist. Orient. 17, 299–328. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hadj-Sadok M. (1949). Descripción del Magreb y de Europa au IIIe-IXe siecle. Argel: Carbonel. [ Google Académico ]

- Hammer MF, Redd AJ, Wood ET, Bonner MR, Jarjanazi H., Karafet T., et al. (2000). Las poblaciones judías y no judías de Oriente Medio comparten un conjunto común de haplotipos bialélicos del cromosoma Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6769–6774. 10.1073/pnas.100115997 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Hansen V. (2012). La Ruta de la Seda: Una Nueva Historia. Nueva York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Google Académico ]

- Hellenthal G., Myers S., Reich D., Busby GBJ, Lipson M., Capelli C., et al. (2016). ¿El aislado genético Kalash? La evidencia de una mezcla reciente. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 98, 396–397. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.12.025 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Jobling M., Hurles ME, Tyler-Smith C. (2013). Genética evolutiva humana: orígenes, pueblos y enfermedades. Nueva York, NY: Garland Science. [ Google Académico ]

- Khordadhbeh I. (1889). El Libro de los Caminos y los Reinos (Kitab al-Masalik Wa-'al-Mamalik), pág. 114 en la Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, editado por de Goeje. Leiden: Brill. [ Google Académico ]

- King RD (2001). La paradoja de la creatividad en la diáspora: el yidis y la identidad judía. Stud. Ling. Sci. 31, 213–229. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kraemer RS (2010). Testigos poco fiables: Religión, género e historia en el Mediterráneo grecorromano. Nueva York, NY: Oxford University Press; 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199743186.001.0001 [ DOI ] [ Google Académico ]

- Lazaridis I., Nadel D., Rollefson G., Merrett DC, Rohland N., Mallick S., et al. (2016). Perspectivas genómicas sobre el origen de la agricultura en el antiguo Cercano Oriente. Nature 536, 419–424. 10.1038/nature19310 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Li JZ, Absher DM, Tang H., Southwick AM, Casto AM, Ramachandran S., et al. (2008). Relaciones humanas mundiales inferidas a partir de patrones de variación genómica. Science 319, 1100–1104. 10.1126/science.1153717 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Marshall S., Das R., Pirooznia M., Elhaik E. (2016). Reconstrucción de la historia de la población drusa. Sci. Rep. 6:35837. 10.1038/srep35837 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Novembre J., Johnson T., Bryc K., Kutalik Z., Boyko AR, Auton A., et al. (2008). Los genes reflejan la geografía en Europa. Nature 456, 98–101. 10.1038/nature07331 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Novembre J., Stephens M. (2008). Interpretación de los análisis de componentes principales de la variación genética poblacional espacial. Nat . Genet. 40, 646–649. 10.1038/ng.139 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Ostrer H. (2001). Un perfil genético de las poblaciones judías contemporáneas. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 891–898. 10.1038/35098506 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Ostrer H. (2012). Legado: Una historia genética del pueblo judío. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Patai R. (1983). Sobre el folclore judío. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press. [ Google Académico ]

- Patterson NJ, Moorjani P., Luo Y., Mallick S., Rohland N., Zhan Y., et al. (2012). Mezcla antigua en la historia humana. Genética 192, 1065–1093. 10.1534/genetics.112.145037 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Rabinowitz LI (1945). Las rutas de los radanitas. Jew. Q. Rev. 35, 251–280. 10.2307/1452187 [ DOI ] [ Google Académico ]

- Rabinowitz LI (1948). Aventureros mercaderes judíos: Un estudio de los radanitas. Londres: Goldston. [ Google Scholar ]

- Robert JN (2014). De Roma a la China. Sur les Routes de la soie au Temps des Césars. París: Les Belles Lettres. [ Google Académico ]

- Sand S. (2009). La invención del pueblo judío. Londres: Verso. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sand S. (2011). Las palabras y la tierra: Intelectuales israelíes y el mito nacionalista. Los Ángeles, CA: Semiotext(e). [ Google Scholar ]

- Telegdi Z. (1933). Un Talmudi Irodalom iráni Kölcsönszavainak Hangtana. Budapest: Kertész József Ny. [ Google Académico ]

- van Straten J. (2004). Migraciones judías de Alemania a Polonia: la hipótesis de Renania revisada. Mankind Q. 44, 367–384. [ Google Scholar ]

- van Straten J. (2007). Judería polaca moderna temprana: la hipótesis de Renania revisada. Hist. Methods 40, 39–50. 10.3200/HMTS.40.1.39-50 [ DOI ] [ Google Académico ]

- van Straten J., Snel H. (2006). El «milagro demográfico» judío en la Europa del siglo XIX: ¿realidad o ficción? Hist. Methods 39, 123–131. 10.3200/HMTS.39.3.123-131 [ DOI ] [ Google Académico ]

- Veeramah KR, Tönjes A., Kovacs P., Gross A., Wegmann D., Geary P., et al. (2011). Variación genética en los sorbios de Alemania Oriental en el contexto de una diversidad genética europea más amplia. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 19, 995–1001. 10.1038/ejhg.2011.65 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Weinreich M. (2008). Historia del yidis. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Google Académico ]

- Wexler P. (1991). Yidis, la decimoquinta lengua eslava. Un estudio de la transición lingüística parcial del judeosorbio al alemán. Int. J. Soc. Lang. 1991, 9–150, 215–225. 10.1515/ijsl.1991.91.9 [ DOI ] [ Google Académico ]

- Wexler P. (1993). Los judíos asquenazíes: un pueblo eslavo-turco en busca de una identidad judía. Columbus, OH: Slavica. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wexler P. (1996). Los orígenes no judíos de los judíos sefardíes. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. [ Google Académico ]

- Wexler P. (2010). ¿Los judíos asquenazíes (es decir, “escitas”) son originarios de Irán y el Cáucaso y son yiddish eslavos?, en Sprache und Leben der frühmittelalterlichen Slaven: Festschrift für Radoslav Katičić zum 80 Geburtstag, eds Stadnik-Holzer E., Holzer G. (Frankfurt: Peter Lang;), 189–216. [ Google Académico ]

- Wexler P. (2011). Una población irano-turco-eslava encubierta y sus dos lenguas eslavas encubiertas: los judíos asquenazíes (escitas), el yidis y el hebreo. Zbornik Matice srpske za Slavistiku 80, 7–46. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wexler P. (2012). Relexificación en yiddish: ¿una lengua eslava disfrazada de dialecto del alto alemán?, en Studien zu Sprache, Literatur und Kultur bei den Slaven: Gedenkschrift für George, Y. Shevelov aus Anlass seines 100. Geburtstages und 10. Todestages, eds Danylenko A., Vakulenko SH (München, Berlín: Verlag Otto Sagner; ), 212–230. [ Google Académico ]

- Wexler P. (2016). Retención transfronteriza de las lenguas túrquicas e iraníes en las tierras eslavas occidentales y orientales y más allá: una clasificación provisional, en The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders, eds. Kamusella T., Nomachi M., Gibson C. (Londres: Palgrave Macmillan), 8–25. [ Google Académico ]

- Wexler P. (2017). Una mirada a lo olvidado. (Los componentes iraníes y otros componentes asiáticos y africanos de los yidis eslavos, iraníes y turcos, y su léxico hebreo común a lo largo de las Rutas de la Seda). [ Google Scholar ]

- Xue J., Lencz T., Darvasi A., Pe'er I., Carmi S. (2017). El tiempo y el lugar de la mezcla europea en la historia judía asquenazí. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006644. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006644 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Yang WY, Novembre J., Eskin E., Halperin E. (2012). Un enfoque basado en modelos para el análisis de la estructura espacial en datos genéticos. Nat. Genet. 44, 725–731. 10.1038/ng.2285 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

- Yang WY, Platt A., Chiang CW-K., Eskin E., Novembre J., Pasaniuc B. (2014). Localización espacial de ancestros recientes de individuos mestizos. G3 (Bethesda) 4, 2505–2518. 10.1534/g3.114.014274 [ DOI ] [ Artículo gratuito de PMC ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Académico ]

Abstract

Recently, the geographical origins of Ashkenazic Jews (AJs) and their native language Yiddish were investigated by applying the Geographic Population Structure (GPS) to a cohort of exclusively Yiddish-speaking and multilingual AJs. GPS localized most AJs along major ancient trade routes in northeastern Turkey adjacent to primeval villages with names that resemble the word “Ashkenaz.” These findings were compatible with the hypothesis of an Irano-Turko-Slavic origin for AJs and a Slavic origin for Yiddish and at odds with the Rhineland hypothesis advocating a Levantine origin for AJs and German origins for Yiddish. We discuss how these findings advance three ongoing debates concerning (1) the historical meaning of the term “Ashkenaz;” (2) the genetic structure of AJs and their geographical origins as inferred from multiple studies employing both modern and ancient DNA and original ancient DNA analyses; and (3) the development of Yiddish. We provide additional validation to the non-Levantine origin of AJs using ancient DNA from the Near East and the Levant. Due to the rising popularity of geo-localization tools to address questions of origin, we briefly discuss the advantages and limitations of popular tools with focus on the GPS approach. Our results reinforce the non-Levantine origins of AJs.

Keywords: Yiddish, Ashkenazic Jews, Ashkenaz, geographic population structure (GPS), Archaeogenetics, Rhineland hypothesis, ancient DNA

Background

The geographical origin of the Biblical “Ashkenaz,” Ashkenazic Jews (AJs), and Yiddish, are among the longest standing questions in history, genetics, and linguistics.

Uncertainties concerning the meaning of “Ashkenaz” arose in the Eleventh century when the term shifted from a designation of the Iranian Scythians to become that of Slavs and Germans and finally of “German” (Ashkenazic) Jews in the Eleventh to Thirteenth centuries (Wexler, 1993). The first known discussion of the origin of German Jews and Yiddish surfaced in the writings of the Hebrew grammarian Elia Baxur in the first half of the Sixteenth century (Wexler, 1993).

It is well established that history is also reflected in the DNA through relationships between genetics, geography, and language (e.g., Cavalli-Sforza, 1997; Weinreich, 2008). Max Weinreich, the doyen of the field of modern Yiddish linguistics, has already emphasized the truism that the history of Yiddish mirrors the history of its speakers. These relationships prompted Das et al. (2016) to address the question of Yiddish origin by analyzing the genomes of Yiddish-speaking AJs, multilingual AJs, and Sephardic Jews using the Geographical Population Structure (GPS), which localizes genomes to where they experienced the last major admixture event. GPS traced nearly all AJs to major ancient trade routes in northeastern Turkey adjacent to four primeval villages whose names resemble “Ashkenaz:” İşkenaz (or Eşkenaz), Eşkenez (or Eşkens), Aşhanas, and Aschuz. Evaluated in light of the Rhineland and Irano-Turko-Slavic hypotheses (Das et al., 2016, Table 1) the findings supported the latter, implying that Yiddish was created by Slavo-Iranian Jewish merchants plying the Silk Roads. We discuss these findings from historical, genetic, and linguistic perspectives and calculate the genetic similarity of AJs and Middle Eastern populations to ancient genomes from Anatolia, Iran, and the Levant. We lastly review briefly the advantages and limitation of bio-localization tools and their application in genetic research.

Table 1.

Major open questions regarding the origin of the term “Ashkenaz,” AJs, and Yiddish as explained by two competing hypotheses.

The genetic evidence produced by Das et al. (2016) is shown in the last column.

The historical meaning of ashkenaz

“Ashkenaz” is one of the most disputed Biblical placenames. It appears in the Hebrew Bible as the name of one of Noah's descendants (Genesis 10:3) and as a reference to the kingdom of Ashkenaz, prophesied to be called together with Ararat and Minnai to wage war against Babylon (Jeremiah 51:27). In addition to tracing AJs to the ancient Iranian lands of Ashkenaz and uncovering the villages whose names may derive from “Ashkenaz,” the partial Iranian origin of AJs, inferred by Das et al. (2016), was further supported by the genetic similarity of AJs to Sephardic Mountain Jews and Iranian Jews as well as their similarity to Near Eastern populations and simulated “native” Turkish and Caucasus populations.

There are good grounds, therefore, for inferring that Jews who considered themselves Ashkenazic adopted this name and spoke of their lands as Ashkenaz, since they perceived themselves as of Iranian origin. That we find varied evidence of the knowledge of Iranian language among Moroccan and Andalusian Jews and Karaites prior to the Eleventh century is a compelling point of reference to assess the shared Iranian origins of Sephardic and Ashkenazic Jews (Wexler, 1996). Moreover, Iranian-speaking Jews in the Caucasus (the so-called Juhuris) and Turkic-speaking Jews in the Crimea prior to World War II called themselves “Ashkenazim” (Weinreich, 2008).

The Rhineland hypothesis cannot explain why a name that denotes “Scythians” and was associated with the Near East became associated with German lands in the Eleventh to Thirteenth centuries (Wexler, 1993). Aptroot (2016) suggested that Jewish immigrants in Europe transferred Biblical names onto the regions in which they settled. This is unconvincing. Biblical names were used as place names only when they had similar sounds. Not only Germany and Ashkenaz do not share similar sounds, but Germany was already named “Germana,” or “Germamja” in the Iranian (“Babylonian”) Talmud (completed in the Fifth century A.D.) and, not surprisingly, was associated with Noah's grandson Gomer (Talmud, Yoma 10a). Name adoption also occurred when the exact place names were in doubt as in the case of Sefarad (Spain). This is not the case here, as Aptroot too notes, since “Ashkenaz” had a known and clear geographical affiliation (Table 1). Finally, Germany was known to French scholars like the RaDaK (1160–1235) as “Almania” (Sp. Alemania, Fr. Allemagne), after the Almani tribes, a term that was also adopted by Arab scholars. Had the French scholar Rashi (1040?-1105), interpreted aškenaz as “Germany,” it would have been known to the RaDaK who used Rashi's symbols. Therefore, Wexler's proposal that Rashi used aškenaz in the meaning of “Slavic” and that the term aškenaz assumed the solitary meaning “German lands” only after the Eleventh century in Western Europe as a result of the rise of Yiddish, is more reasonable (Wexler, 2011). This is also supported by Das et al.'s major findings of the only known primeval villages whose names derive from the word “Ashkenaz” located in the ancient lands of Ashkenaz. Our inference is therefore supported by historical, linguistic, and genetic evidence, which has more weight as a simple origin that can be easily explained than a more complex scenario that involves multiple translocations.

The genetic structure of ashkenazic jews

AJs were localized to modern-day Turkey and found to be genetically closest to Turkic, southern Caucasian, and Iranian populations, suggesting a common origin in Iranian “Ashkenaz” lands (Das et al., 2016). These findings were more compatible with an Irano-Turko-Slavic origin for AJs and a Slavic origin for Yiddish than with the Rhineland hypothesis, which lacks historical, genetic, and linguistic support (Table 1) (van Straten, 2004; Elhaik, 2013). The findings have also highlighted the strong social-cultural and genetic bonds of Ashkenazic and Iranian Judaism and their shared Iranian origins (Das et al., 2016).

Thus far, all analyses aimed to geo-localize AJs (Behar et al., 2013, Figure 2B; Elhaik, 2013, Figure 4; Das et al., 2016, Figure 4) identified Turkey as the predominant origin of AJs, although they used different approaches and datasets, in support of the Irano-Turko-Slavic hypothesis (Figure 1A, Table 1). The existence of both major Southern European and Near Eastern ancestries in AJ genomes are also strong indictors of the Irano-Turko-Slavic hypothesis provided the Greco-Roman history of the region southern to the Black Sea (Baron, 1937; Kraemer, 2010). Recently, Xue et al. (2017) applied GLOBETROTTER to a dataset of 2,540 AJs genotyped over 252,358 SNPs. The inferred ancestry profile for AJs was 5% Western Europe, 10% Eastern Europe, 30% Levant, and 55% Southern Europe (a Near East ancestry was not considered by the authors). Elhaik (2013) portrayed a similar profile for European Jews, consisting of 25–30% Middle East and large Near Eastern–Caucasus (32–38%) and West European (30%) ancestries. Remarkably, Xue et al. (2017) also inferred an “admixture time” of 960–1,416 AD (≈24–40 generations ago), which corresponds to the time AJs experienced major geographical shifts as the Judaized Khazar kingdom diminished and their trading networks collapsed forcing them to relocate to Europe (Das et al., 2016). The lower boundary of that date corresponds to the time Slavic Yiddish originated, to the best of our knowledge.

Figure 1.

The localization of AJs and their ancient admixture proportions compared to neighboring populations. (A) Geographical predictions of individuals analyzed in three separate studies employing different tools: Elhaik (2013, Figure 4) (blue), Behar et al. (2013, Figure 2B) (red), and Das et al. (2016, Figure 4) (dark green for AJs who have four AJ grandparents and light green for the rest) are shown. Color matching mean and standard deviation (bars) of the longitude and latitude are shown for each cohort. Since we were unsuccessful in obtaining the data points of Behar et al. (2013, Figure 2B) from the corresponding author, we procured 78% of the data points from their figure. Due to the low quality of their figure we were unable to reliably extract the remaining data points. (B) Supervised ADMIXTURE results. For brevity, subpopulations were collapsed. The x axis represents individuals. Each individual is represented by a vertical stacked column of color-coded admixture proportions that reflect genetic contributions from ancient Hunter-Gatherer, Anatolian, Levantine, and Iranian individuals.

The non-Levantine origin of AJs is further supported by an ancient DNA analysis of six Natufians and a Levantine Neolithic (Lazaridis et al., 2016), some of the most likely Judaean progenitors (Finkelstein and Silberman, 2002; Frendo, 2004). In a principle component analysis (PCA), the ancient Levantines clustered predominantly with modern-day Palestinians and Bedouins and marginally overlapped with Arabian Jews, whereas AJs clustered away from Levantine individuals and adjacent to Neolithic Anatolians and Late Neolithic and Bronze Age Europeans. To evaluate these findings, we inferred the ancient ancestries of AJs using the admixture analysis described in Marshall et al. (2016). Briefly, we analyzed 18,757 autosomal SNPs genotyped in 46 Palestinians, 45 Bedouins, 16 Syrians, and eight Lebanese (Li et al., 2008) alongside 467 AJs [367 AJs previously analyzed and 100 individuals with AJ mother) (Das et al., 2016) that overlapped with both the GenoChip (Elhaik et al., 2013) and ancient DNA data (Lazaridis et al., 2016). We then carried out a supervised ADMIXTURE analysis (Alexander and Lange, 2011) using three East European Hunter Gatherers from Russia (EHGs) alongside six Epipaleolithic Levantines, 24 Neolithic Anatolians, and six Neolithic Iranians as reference populations (Table S0). Remarkably, AJs exhibit a dominant Iranian (

The linguistic debate concerning formation of yiddish

The hypothesis that Yiddish has a German origin ignores the mechanics of relexification, the linguistic process which produced Yiddish and other “Old Jewish” languages (i.e., those created by the Ninth to Tenth century). Understanding how relexification operates is essential to understanding the evolution of languages. This argument has a similar context to that of the evolution of powered flight. Rejecting the theory of evolution may lead one to conclude that birds and bats are close relatives. By disregarding the literature on relexification and Jewish history in the early Middle Ages, authors (e.g., Aptroot, 2016; Flegontov et al., 2016) reach conclusions that have weak historical support. The advantage of a geo-localization analysis is that it allows us to infer the geographical origin of the speakers of Yiddish, where they resided and with whom they intermingled, independently of historical controversies, which provides a data driven view on the question of geographical origins. This allows an objective review of potential linguistic influences on Yiddish (Table 1), which exposes the dangers in adopting a “linguistic creationism” view in linguistics.

The historical evidence in favor of an Irano-Turko-Slavic origin for Yiddish is paramount (e.g., Wexler, 1993, 2010). Jews played a major role on the Silk Roads in the Ninth to Eleventh century. In the mid-Ninth century, in roughly the same years, Jewish merchants in both Mainz and at Xi'an received special trading privileges from the Holy Roman Empire and the Tang dynasty court (Robert, 2014). These roads linked Xi'an to Mainz and Andalusia, and further to sub-Saharan Africa and across to the Arabian Peninsula and India-Pakistan. The Silk Roads provided the motivation for Jewish settlement in Afro-Eurasia in the Ninth to Eleventh centuries since the Jews played a dominant role on these routes as a neutral trading guild with no political agendas (Gil, 1974; Cansdale, 1996, 1998). Hence, the Jewish traders had contact with a wealth of languages in the areas that they traversed (Hadj-Sadok, 1949; Khordadhbeh, 1889; Hansen, 2012; Wexler TBD), which they brought back to their communities nested in major trading hubs (Rabinowitz, 1945, 1948; Das et al., 2016). The central Eurasian Silk Roads were controlled by Iranian polities, which provided opportunities for Iranian-speaking Jews, who constituted the overwhelming bulk of the world's Jews from the time of Christ to the Eleventh century (Baron, 1952). It should not come as a surprise to find that Yiddish (and other Old Jewish languages) contains components and rules from a large variety of languages, all of them spoken on the Silk Roads (Khordadhbeh, 1889; Wexler, 2011, 2012, 2017).

In addition to language contacts, the Silk Roads also provided the motivation for widespread conversion to Judaism by populations eager to participate in the extremely lucrative trade, which had become a Jewish quasi-monopoly along the trade routes (Rabinowitz, 1945, 1948; Baron, 1957). These conversions are discussed in Jewish literature between the Sixth and Eleventh centuries, both in Europe and Iraq (Sand, 2009; Kraemer, 2010). Yiddish and other Old Jewish languages were all created by the peripatetic merchants as secret languages that would isolate them from their customers and non-Jewish trading partners (Hadj-Sadok, 1949; Gil, 1974; Khordadhbeh, 1889; Cansdale, 1998; Robert, 2014). The study of Yiddish genesis, thereby, necessitates the study of all the Old Jewish languages of this time period.

There is also a quantifiable amount of Iranian and Turkic elements in Yiddish. The Babylonian Talmud, completed by the Sixth century A.D., is rich in Iranian linguistic, legalistic, and religious influences. From the Talmud, a large Iranian vocabulary has entered Hebrew and Judeo-Aramaic, and from there spread to Yiddish. This corpus has been known since the 1930s and is common knowledge to Talmud scholars (Telegdi, 1933). In the Khazar Empire, the Eurasian Jews, plying the Silk Roads, became speakers of Slavic—an important language because of the trading activities of the Rus' (pre-Ukrainians) with whom the Jews were undoubtedly allied on the routes linking Baghdad and Bavaria. This is evident by the existence of newly invented Hebroidism, inspired by Slavic patterns of discourse in Yiddish (Wexler, 2010).

We advocate for implementing a more evolutionary understanding in linguistics. That includes giving more attention to the linguistic process that alter languages (e.g., relexification) and acquiring more competence in other languages and histories. When studying the origin of Ashkenazic Jews and Yiddish, such knowledge should include the history of the Silk Roads and Irano-Turkish languages.

Inference of geographical origins

Deciphering the origin of human populations is not a new challenge for geneticists, yet only in the past decade high-throughput genetic data were harnessed to answer these questions. Here, we briefly discuss the differences between the available tools based on identity by distance. Existing PCA or PCA-like approaches (e.g., Novembre et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2012) can localize Europeans to countries (understood as the last place where major admixture event took place or the place where the four ancestors of “unmixed” individuals came from) with less than 50% accuracy (Yang et al., 2012). The limitations of PCA (discussed in Novembre and Stephens, 2008) appear to be inherent in the framework where continental populations plotted along the two primary PCs cluster in the vertices of a triangle-like shape and the remaining populations cluster along or within the edges (e.g., Elhaik et al., 2013). There is therefore reason to question the applicability of ambitious PCA-based methods (Yang et al., 2012, 2014) aiming to infer multiple ancestral locations outside of Europe. Overall, accurate localization of worldwide individuals remains a significant challenge (Elhaik et al., 2014).

The GPS framework assumes that humans are mixed and that their genetic variation (admixture) can be modeled by the proportion of genotypes assigned to any number of fixed regional putative ancestral populations (Elhaik et al., 2014). GPS employs a supervised ADMIXTURE analysis where the admixture components are fixed, which allows evaluating both the test individuals and reference populations against the same putative ancestral populations. GPS infers the geographical coordinates of an individual by matching their admixture proportions with those of reference populations. Reference populations are populations known to reside in a certain geographical region for a substantial period of time in a time frame of hundreds to a thousand years and can be predicted to their geographical locations while absent from the reference population panel (Das et al., 2016). The final geographic location of a test individual is determined by converting the genetic distance of the individual to m reference populations into geographic distances (Elhaik et al., 2014). Intuitively, the reference populations can be thought of as “pulling” the individual in their direction with a strength proportional to their genetic similarity until a consensus is reached (Figure S1). Interpreting the results, particularly when the predicted location differs from the contemporary location of the studied population, demands cautious.

Population structure is affected by biological and demographic processes like genetic drift, which can act rapidly on small, relatively isolated populations, as opposed to large non-isolated populations, and migration, which occurs more frequently (Jobling et al., 2013). Understanding the geography-admixture relationships necessitates knowing how relative isolation and migration history affected the allele frequencies of populations. Unfortunately, oftentimes we lack information about both processes. GPS addresses this problem by analyzing the relative proportions of admixture in a global network of reference populations that provide us with different “snapshots” of historical admixture events. These global admixture events occurred at different times through different biological and demographic processes, and their long-lasting effect is related to our ability to associate an individual with their matching admixture event.

In relatively isolated populations the admixture event is likely old, and GPS would localize a test individual with their parental population more accurately. By contrast, if the admixture event was recent and the population did not maintain relative isolation, GPS prediction would be erroneous (Figure S2). This is the case of Caribbean populations, whose admixture proportions still reflect the massive Nineteenth and Twentieth centuries' mixture events involving Native Americans, West Europeans, and Africans (Elhaik et al., 2014). While the original level of isolation remains unknown, these two scenarios can be distinguished by comparing the admixture proportions of the test individual and adjacent populations. If this similarity is high, we can conclude that we have inferred the likely location of the admixture event that shaped the admixture proportion of the test individual. If the opposite is true, the individual is either mixed and thereby violates the assumptions of the GPS model or the parental populations do not exist either in GPS's reference panel or in reality. Most of the time (83%) GPS predicted unmixed individuals to their true locations with most of the remaining individuals predicted to neighboring countries (Elhaik et al., 2014).

To understand how migration modifies the admixture proportions of the migratory and host populations, we can consider two simple cases of point or massive migration followed by assimilation and a third case of migration followed by isolation. Point migration events have little effect on the admixture proportions of the host population, particularly when it absorbs a paucity of migrants, in which case the migrants' admixture proportions would resemble those of the host population within a few generations and their resting place would represent that of the host population. Massive demographic movements, such as large-scale invasion or migration that affect a large part of the population are rare and create temporal shifts in the admixture proportions of the host population. The host population would temporarily appear as a two-way mixed population, reflecting the components of the host and invading populations (e.g., European and Native American, in the case of Puerto Ricans) until the admixture proportions would homogenize population-wise. If this process is completed, the admixture signature of this region may be altered and the geographical placement of the host population would represent again the last place where the admixture event took place for both the host and invading populations. GPS would, thereby, predict the host population's location for both populations. Populations that migrate from A to B and maintain genetic isolation would be predicted to point A in the leave-one-out population analysis. While human migrations are not uncommon, maintaining a perfect genetic isolation over a long period of time is very difficult (e.g., Veeramah et al., 2011; Behar et al., 2012; Elhaik, 2016; Hellenthal et al., 2016), and GPS predictions for the vast majority of worldwide populations indicate that these cases are indeed exceptional (Elhaik et al., 2014). Despite of its advantages, GPS has several limitations. First, it yields the most accurate predictions for unmixed individuals. Second, using migratory or highly mixed populations (both are detectable through the leave-one-out population analysis) as reference populations may bias the predictions. Further developments are necessary to overcome these limitations and make GPS applicable to mixed population groups (e.g., African Americans).

Conclusion

The meaning of the term “Ashkenaz” and the geographical origins of AJs and Yiddish are some of the longest standing questions in history, genetics, and linguistics. In our previous work we have identified “ancient Ashkenaz,” a region in northeastern Turkey that harbors four primeval villages whose names resemble Ashkenaz. Here, we elaborate on the meaning of this term and argue that it acquired its modern meaning only after a critical mass of Ashkenazic Jews arrived in Germany. We show that all bio-localization analyses have localized AJs to Turkey and that the non-Levantine origins of AJs are supported by ancient genome analyses. Overall, these findings are compatible with the hypothesis of an Irano-Turko-Slavic origin for AJs and a Slavic origin for Yiddish and contradict the predictions of Rhineland hypothesis that lacks historical, genetic, and linguistic support (Table 1).

Author contributions

EE conceived the paper. MP processed the ancient DNA data. RD and EE carried out the analyses. EE co-wrote it with PW and RD. All authors approved the paper.

Conflict of interest statement

EE is a consultant for DNA Diagnostic Centre. The other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer PF declared a past co-authorship with one of the authors to the handling Editor, who ensured that the process nevertheless met the standards of a fair and objective review.

Acknowledgments

EE was partially supported by The Royal Society International Exchanges Award to EE and Michael Neely (IE140020), MRC Confidence in Concept Scheme award 2014-University of Sheffield to EE (Ref: MC_PC_14115), and a National Science Foundation grant DEB-1456634 to Tatiana Tatarinova and EE. We thank the many public participants for donating their DNA sequences for scientific studies and The Genographic Project's public database for providing us with their data.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fgene.2017.00087/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alexander D. H., Lange K. (2011). Enhancements to the ADMIXTURE algorithm for individual ancestry estimation. BMC Bioinformatics 12:246. 10.1186/1471-2105-12-246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aptroot M. (2016). Yiddish language and Ashkenazic Jews: a perspective from culture, language and literature. Genome Biol. Evol. 8, 1948–1949. 10.1093/gbe/evw131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzmon G., Hao L., Pe'er I., Velez C., Pearlman A., Palamara P. F., et al. (2010). Abraham's children in the genome era: major Jewish diaspora populations comprise distinct genetic clusters with shared Middle Eastern ancestry. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 86, 850–859. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron S. W. (1937). Social and Religious History of the Jews, vol. 1 New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baron S. W. (1952). Social and Religious History of the Jews, vol. 2 New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baron S. W. (1957). Social and Religious History of the Jews, vol. 3. High Middle Ages: Heirs of Rome and Persia. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Behar D. M., Harmant C., Manry J., van Oven M., Haak W., Martinez-Cruz B., et al. (2012). The Basque paradigm: genetic evidence of a maternal continuity in the Franco-Cantabrian region since pre-Neolithic times. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90, 486–493. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar D. M., Metspalu M., Baran Y., Kopelman N. M., Yunusbayev B., Gladstein A., et al. (2013). No evidence from genome-wide data of a Khazar origin for the Ashkenazi Jews. Hum. Biol. 85, 859–900. 10.3378/027.085.0604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sasson H. H. (1976). A History of the Jewish People. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cansdale L. (1996). The Radhanites: ninth century Jewish international traders. Aust. J. Jewish Stud. 10, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cansdale L. (1998). Jews on the Silk Road, in Worlds of the Silk Roads: Ancient and Modern, eds Christian D., Benjamin C. (Turnhout: Brepols; ), 23–30. 10.1484/M.SRS-EB.4.00037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza L. L. (1997). Genes, peoples, and languages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 7719–7724. 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das R., Wexler P., Pirooznia M., Elhaik E. (2016). Localizing Ashkenazic Jews to primeval villages in the ancient Iranian lands of Ashkenaz. Genome Biol. Evol. 8, 1132–1149. 10.1093/gbe/evw046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhaik E. (2013). The missing link of Jewish European ancestry: Contrasting the Rhineland and the Khazarian hypotheses. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 61–74. 10.1093/gbe/evs119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhaik E. (2016). In search of the jüdische Typus: a proposed benchmark to test the genetic basis of Jewishness challenges notions of “Jewish biomarkers.” Front. Genet. 7:141. 10.3389/fgene.2016.00141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhaik E., Greenspan E., Staats S., Krahn T., Tyler-Smith C., Xue Y., et al. (2013). The GenoChip: a new tool for genetic anthropology. Genome Biol. Evol. 5, 1021–1031. 10.1093/gbe/evt066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhaik E., Tatarinova T., Chebotarev D., Piras I. S., Maria Calò C., De Montis A., et al. (2014). Geographic population structure analysis of worldwide human populations infers their biogeographical origins. Nat. Commun. 5:3513 10.1038/ncomms4513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk R. (2006). Zionism and the Biology of Jews (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Resling. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein I., Silberman N. A. (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Flegontov P., Kassian A., Thomas M. G., Fedchenko V., Changmai P., Starostin G., et al. (2016). Pitfalls of the geographic population structure (GPS) approach applied to human genetic history: a case study of Ashkenazi Jews. Genome Biol. Evol. 8, 2259–2265. 10.1093/gbe/evw162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frendo A. J. (2004). Back to basics: a holistic approach to the problem of the emergence of ancient Israel, in Search of Pre-Exilic Israel, ed Day J. (New York, NY: T&T Clark International; ), 41–64. 10.1097/00152193-200410000-00004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gil M. (1974). The Rādhānite merchants and the land of Rādhān. J. Econ. Soc. Hist. Orient. 17, 299–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hadj-Sadok M. (1949). Description du Maghreb et de l'Europe au IIIe-IXe siecle. Algiers: Carbonel. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer M. F., Redd A. J., Wood E. T., Bonner M. R., Jarjanazi H., Karafet T., et al. (2000). Jewish and Middle Eastern non-Jewish populations share a common pool of Y-chromosome biallelic haplotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6769–6774. 10.1073/pnas.100115997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen V. (2012). The Silk Road: A New History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hellenthal G., Myers S., Reich D., Busby G. B. J., Lipson M., Capelli C., et al. (2016). The Kalash genetic isolate? the evidence for recent admixture. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 98, 396–397. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobling M., Hurles M. E., Tyler-Smith C. (2013). Human Evolutionary Genetics: Origins, Peoples and Disease. New York, NY: Garland Science. [Google Scholar]

- Khordadhbeh I. (1889). The Book of Roads and Kingdoms (Kitab al-Masalik Wa-'al-Mamalik), p. 114 in Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, Edited by de Goeje. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- King R. D. (2001). The paradox of creativity in diaspora: the Yiddish language and Jewish identity. Stud. Ling. Sci. 31, 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer R. S. (2010). Unreliable Witnesses: Religion, Gender, and History in the Greco-Roman Mediterranean. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199743186.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis I., Nadel D., Rollefson G., Merrett D. C., Rohland N., Mallick S., et al. (2016). Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East. Nature 536, 419–424. 10.1038/nature19310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. Z., Absher D. M., Tang H., Southwick A. M., Casto A. M., Ramachandran S., et al. (2008). Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome-wide patterns of variation. Science 319, 1100–1104. 10.1126/science.1153717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S., Das R., Pirooznia M., Elhaik E. (2016). Reconstructing Druze population history. Sci. Rep. 6:35837. 10.1038/srep35837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novembre J., Johnson T., Bryc K., Kutalik Z., Boyko A. R., Auton A., et al. (2008). Genes mirror geography within Europe. Nature 456, 98–101. 10.1038/nature07331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novembre J., Stephens M. (2008). Interpreting principal component analyses of spatial population genetic variation. Nat. Genet. 40, 646–649. 10.1038/ng.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrer H. (2001). A genetic profile of contemporary Jewish populations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 891–898. 10.1038/35098506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrer H. (2012). Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patai R. (1983). On Jewish Folklore. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson N. J., Moorjani P., Luo Y., Mallick S., Rohland N., Zhan Y., et al. (2012). Ancient admixture in Human history. Genetics 192, 1065–1093. 10.1534/genetics.112.145037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz L. I. (1945). The routes of the Radanites. Jew. Q. Rev. 35, 251–280. 10.2307/1452187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz L. I. (1948). Jewish Merchant Adventurers: A Study of the Radanites. London: Goldston. [Google Scholar]

- Robert J. N. (2014). De Rome à la Chine. Sur les Routes de la soie au Temps des Césars. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. [Google Scholar]

- Sand S. (2009). The Invention of the Jewish People. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Sand S. (2011). The Words and the Land: Israeli Intellectuals and the Nationalist Myth. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e). [Google Scholar]

- Telegdi Z. (1933). A Talmudi Irodalom iráni Kölcsönszavainak Hangtana. Budapest: Kertész József Ny. [Google Scholar]

- van Straten J. (2004). Jewish migrations from Germany to Poland: the Rhineland hypothesis revisited. Mankind Q. 44, 367–384. [Google Scholar]

- van Straten J. (2007). Early modern Polish Jewry the Rhineland hypothesis revisited. Hist. Methods 40, 39–50. 10.3200/HMTS.40.1.39-50 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Straten J., Snel H. (2006). The Jewish “demographic miracle” in nineteenth-century Europe fact or fiction? Hist. Methods 39, 123–131. 10.3200/HMTS.39.3.123-131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veeramah K. R., Tönjes A., Kovacs P., Gross A., Wegmann D., Geary P., et al. (2011). Genetic variation in the Sorbs of eastern Germany in the context of broader European genetic diversity. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 19, 995–1001. 10.1038/ejhg.2011.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich M. (2008). History of the Yiddish Language. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler P. (1991). Yiddish—the fifteenth Slavic language. A study of partial language shift from Judeo-Sorbian to German. Int. J. Soc. Lang. 1991, 9–150, 215–225. 10.1515/ijsl.1991.91.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler P. (1993). The Ashkenazic Jews: a Slavo-Turkic People in Search of a Jewish identity. Colombus, OH: Slavica. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler P. (1996). The Non-Jewish Origins of the Sephardic Jews. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler P. (2010). Do Jewish Ashkenazim (i.e. “Scythians”) originate in Iran and the Caucasus and is Yiddish Slavic?, in Sprache und Leben der frühmittelalterlichen Slaven: Festschrift für Radoslav Katičić zum 80 Geburtstag, eds Stadnik-Holzer E., Holzer G. (Frankfurt: Peter Lang; ), 189–216. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler P. (2011). A covert Irano-Turko-Slavic population and its two covert Slavic languages: The Jewish Ashkenazim (Scythians), Yiddish and ‘Hebrew’. Zbornik Matice srpske za Slavistiku 80, 7–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler P. (2012). Relexification in Yiddish: a Slavic language masquerading as a High German dialect?, in Studien zu Sprache, Literatur und Kultur bei den Slaven: Gedenkschrift für George, Y. Shevelov aus Anlass seines 100. Geburtstages und 10. Todestages, eds Danylenko A., Vakulenko S. H. (München, Berlin: Verlag Otto Sagner; ), 212–230. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler P. (2016). Cross-border Turkic and Iranian language retention in the West and East Slavic lands and beyond: a tentative classification, in The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders, eds Kamusella T., Nomachi M., Gibson C. (London: Palgrave Macmillan; ), 8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler P. (2017). Looking at the overlooked. (The Iranian and other Asian and African components of the Slavic, Iranian and Turkic “Yiddishes” and their common Hebrew lexicon along the Silk Roads). [Google Scholar]

- Xue J., Lencz T., Darvasi A., Pe'er I., Carmi S. (2017). The time and place of European admixture in Ashkenazi Jewish history. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006644. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. Y., Novembre J., Eskin E., Halperin E. (2012). A model-based approach for analysis of spatial structure in genetic data. Nat. Genet. 44, 725–731. 10.1038/ng.2285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]